Monteverde

Walking through Monteverde reserve is like walking through the most perfect fairytale I’ve ever read. The forest on every side is green from the ground to the canopy, moss covering the trunks, and plants upon plants hanging from every bit of bark. Creepers and vines wind their way round the trees, and purple tongued orchids suspend themselves in mid air on flimsy stalks. Tiny streams trickle through mossy rocks and prehistoric ferns that look like mini-palms sprout beside the river-bed, their shade of leaves ruffled by a slight breeze.

Tiny birds nests are built into the banks next to the path, and if you look closely you can see miniature mouths squeaking within. Brown-winged parents with yellow bellies fly past to drop off a grub every few minutes. If you’re lucky, you can look up and in the branches above there will be the magical mystical resplendent quetzal, its long green feathers curving down like a quill from its little fat body.

Some say the fairyland is ruined by the abundance of tourists that this little piece of perfection sees every year. It’s the most touristed place in all of Costa Rica – quite a title to hold. Everyone has it on their list, and many are here to hunt down the quetzal, the notoriously aloof, wonderfully exotic inhabitant of the world’s disappearing cloud forests. A Monteverde guide said that one of his clients was so overwhelmed when she saw a quetzal in the reserve that she literally broke down and cried. Its that emotional. But I have to say I managed to contain my tears after I’d seen a male and female in the trees just metres away from the Monteverde reserve gates.

In my opinion, tourists or no, this is a beautiful corner of the world. Walking through the bosque nuboso trail early on a clear morning is a real experience. You could actually believe that fairies live here. From the entrance, the trail climbs gently through perfect, untouched forest. It seems like its been there for millions of years, holding an ancient, impenetrable memory. Birds hoot from the treetops, but are difficult to spot through the thick greenery.

As the trail climbs, the view of the valley opens out below you, with ridges of dark green falling away towards the towns below. You walk up from the Pacific side, but it’s when you hit the continental divide that the treat comes. On one side of the ridge, the land slopes down towards settlements, but on the Caribbean side, the ridge gives way to a steep slope falling down into a valley surrounded by undisturbed hills. As far as the eye can see, the earth is covered in thick deep green, undisturbed by roads, houses, even human figures. It’s then that you realise the legacy of this park. Tourists are only allowed to set foot in a tiny section of it, but that section does contain some of the most beautiful forest. The 10,500 hectares that make up the reserve are mostly left to their own devices.

The marked paths are easy to follow and if you time it carefully you can have a path to yourself at least for fifteen minutes or so. Many people take tours, which are excellent for spotting animals as the guides really know what they’re talking about, but it doesn’t leave much space for personal communing with nature. If you are desperate to see a quetzal, it’s worthwhile taking a guide. It’s also worthwhile because according to the administration there are 100 mammal species, 400 bird species and 3,000 plant species in this reserve. The guides are all trained biologists who speak English and Spanish and can answer pretty much any question you throw at them. You will find out about the many species of avocado that grow here, the reproductive habits of ferns and the evil-looking tarantula-wasps. These are so-called because they sting a tarantula and inject their eggs inside it. When the eggs hatch, the lavae start to eat the tarantula alive from inside.

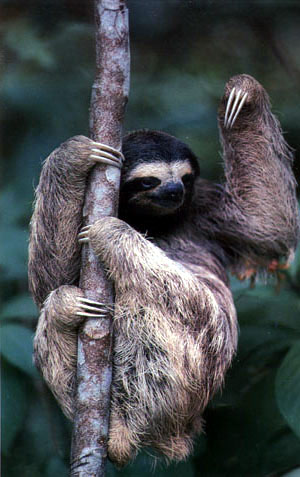

There are trails that lead further on from the triangle of marked trails towards some very little-visited huts, but at the time of writing they were closed and would be for an unspecified time. Closing them consists of putting up a wooden closed sign that is easy to walk past, but be careful if you do choose to go down the paths that they are very slippery and steep. They are also wider than the paths in the forest, making them considerably less interesting. If you sit still for a while, the tranquility does mean that you have the chance of mammals such as nose-bears coming along and snuffling around you for a while.

It should take no longer than a few hours to walk around a good proportion of the 26 or so kilometres of trails in the park. Transport to the reserve is by bus from the village of Santa Elena, with buses leaving town at 6.15, 7.20, 9.20, 11.20, 1 and 2.30, returning at about two hour intervals until 4 o’clock. The cost is 1,000 colones for the return trip.

Entrance is $15.

Santa Elena Reserve

Also a good choice, Santa Elena’s forests are almost as dense and impressive as Monteverde’s, but lack something of the magic. There are fewer tourists, but also less trails. You will be greeted at the gate by the very friendly and enthusiastic Charly, a pet wild pig who was raised by humans and now can’t get enough of them.

Quetzals are a common sight here as well, along with the loud and rare three-wattled bellbird. This bizarre animal has three black things – spaghetti, as the guides call them – hanging off its beak. Take your binoculars and try and see one soon though – their numbers are dwindling drastically. The guides say this is because of global warming. Now that the temperature in the mountains has gone up, other species are climbing to higher altitudes. Predators such as toucans that were never here before now pray on quetzals and three-wattled bell birds, threatening them with extinction.

If you get a nice clear day you have the chance of seeing one of the most impressive views of volcan Arenal available. Take the Caño Negro trail, and look out for a lone bench as you turn a corner. A valley stretches out below, and at the end of it Arenal rises, a perfect cone, whisps of smoke mixing with the white clouds that cling to its summit.

The reserve is managed by the local community in association with Youth Challenge International, a Canadian charity. The charity has a trail named after it, and on this trail there is a thing called ‘the tower’. A large metal construction vaguely resembling a scaffold tower, the lookout point is terribly maintained. Steps are loose, hinges are giving way, and half of the top platform clearly rusted into nothingness a short while ago. Be careful if you want to go up it.

Entrance is $12, guided tours are $15, and can be booked in Santa Elena town. Buses leave from in town and go at 6:30, 8:30, 10:30, 12:30 and 3:00PM returning at 11:00AM, 1:00PM and 4:00PM. It costs 1,000 colones each way.

San Luis Waterfall

If you don’t have transportation to get to this lovely waterfall, be prepared. It’s a good 6 kilometres uphill on the road from Santa Elena towards Monteverde reserve, then another 4 or so steeply downhill after you take the right-hand turn marked San Luis. Then it’s another at least three ascending to the waterfall.

Entrance fee to the little trail is $8, and from the entrance huts the trails is not very long. Reaching the waterfall itself, you catch your breath twice. As you approach, it seems to be a nice thin waterfall falling from a cut in the cliffs into a small clear pool, but a few steps more and you realise it’s twice the height you originally thought, falling in two steps through the carved black rocks.

If it’s a hot day the trip is worth it for a cool down in the pools. If you don’t have transportation it’s usually possible to hitch rides on the roads to and from the waterfall – people are understanding about the hills!

But if you do walk, you get the added bonus of a spectacular view of the gulf of Nicoya. Standing at the lookout point on the road towards San Luis, at first its hard to believe that the shimmering blanket in the distance really is the sea. Dark island float in it, and you can see all the way to the Peninsula on the other side, curving round to make the gulf look almost like a lake.

Santa Elena Town

Small and definitely gringofied, this little community centres on a street full of restaurants. There are some decent eating choices here such as the Tree House, but it’s not cheap. There is one soda for the hard-up. If you didn’t see the animals you wanted to see then there’s always the ranarium, serpentarium, insect museum and butterfly garden, not to mention the orchid nursery.

Monteverde is famed for two things other than the nature: ice cream and cheese. Having actually tasted what cheese is meant to be like, this stuff still doesn’t cut the mustard, though i’d say it’s slightly better than the regular plasticky crap in the stores. Monteverde’s sharp cheddar is not too bad. The other stuff with lots of herbs in really just has a lot of salt in it. The Monteverde cheese factory has a store in it with all of the varieties. It also gives tours.

The ice cream is better – it is very creamy and doesn’t taste of a huge amount, but it’s quite satisfying. Choose something with a flavour you can’t miss, like mint choc chip. It can be bought from the heladeria in the middle of town, Sabores on the road to Monteverde reserve, or at the factory itself.

If you must do a canopy tour, there is plenty of choice around here. Just try to avoid disturbing the monkeys too much with your yodelling when you are swinging through their natural habitat.

Places to stay:

Monteverde Backpackers

Only a year old, this little place is affiliated to Pangea, a San José based hostel, which makes it slightly more expensive at $10 a dorm bed. The house is homely though, with sofas, a TV and two computers with free internet. A friendly, bilingual father-son team run the place and can help out with tours, buses and whatnot. The dorms sleep six and have private bathrooms – there’s usually a good bunch of people around to chat to. A small kitchen can be used if you want to avoid the expensive restaurants, and the supermarket is just steps from the door. Telephone: 2645-5844

Pension Santa Elena

Always full, with people lounging in rocking chairs and hammocks on the porch. This place is slightly cheaper at between $6. Telephone: 2645-6240

Buses to Santa Elena/Monteverde leave San José daily at 6.30 a.m. and 2.30 a.m., returning at the same times.

Filed under: hiking, Traveling, wildlife | Tagged: avocados, backpacers, canopy tour, cheddar, cheese, climate change, extinction, ferns, guide, hiking, huts, ice cream, monteverde, nose bear, orchids, pension santa elena, quetzal, refuges, san luis waterfall, santa elena, three-wattled bellbird, tours, trails, transport, wild pig | Leave a comment »

You must be logged in to post a comment.